Innumerable Voices is a monthly column profiling short fiction writers and exploring speculative fiction themes in their many permutations. The column will discuss stellar genre work from both fresh and established writers who don’t have short fiction collections or novel-length works, but who actively contribute to anthologies and magazines.

Short fiction is where experimentation and innovation happens in genre, and it’s served as a stepping stone for many a beloved writer’s career. At the same time, it’s easy for good work and strong viewpoints to fall through the cracks and not receive the recognition they deserve. This column will signal boost these voices and guide you through the rabbit hole to discover some new favorite writers…

As this serves as the introduction to the Innumerable Voices column, I’ll hover a bit in the beginning to lay down the rules by which I’m playing. Short fiction writers without collected works are often a one-piece experience in the context of a magazine or anthology where their story/novelette/novella converses with the rest. It’s not enough of a foundation to formulate a distinct opinion about a writer and their fiction. This column will provide an overview of an author’s existing body of work as if it’s published as a collection, to give you a better understanding of each month’s featured author. Links to magazines and anthologies for each story are available as footnotes. Chances are I’ll discuss the stories at length, and mild spoilers will be revealed.

As a child, I experienced a special communion whenever I sat to watch short animations based on the Grimm’s Fairy Tales or read One Thousand and One Nights. My whole being would thrum. In those moments, I was a string pulled taut and vibrated along with every word at a frequency that made me quiver to my core. I’m not of any faith, but this is the closest I’ve come to a religious experience—when I first acquainted myself with the raw power that stories wield.

There’s this heavy, venerable simplicity, a result of accreted retellings, that you recognize the moment you hear a story that’s been repeated over centuries. Shveta Thakrar draws on such power to tell her own truth, give voice to her heritage. After all, the world brims with stories. There are these branches, old as humanity, heavy with fruit that has trapped beneath its rind generations of storytelling traditions, lore and deep truths about being human. All unattended for far too long. In her biography, Thakrar describes herself as “a South Asian-flavored fantasy, social justice activist, and part-time nagini”—an apt description, which can be applied to her writing as well.

A favorite short story of mine where it’s easy to see Thakrar’s great love for Indian folklore is a retelling of the fairy tale “Tatterhood,” titled “Lavanya and Deepika.”[1] The title characters are two sisters born via the magic of a yaksha to a rani, who traded her rose garden to have children without a husband—one of crimson skin and thorns like a rose, the other the dark hues of earth. In fairy tales, conflict often arises from the rivalry between women, whether it’s abusive mothers, cruel stepsisters or sibling competitiveness that drives the story. Thakrar is careful to avoid these pitfalls and portrays cordial familial relationships, which stands out especially since Lavanya inhabits the realm of the supernatural far more than her human sister with her thorn skin and leaf hair. Female friendship—whether it’s between sisters, mothers and daughters, or lovers—finds itself a focal point in Thakrar’s work.

“Lavanya and Deepika” doesn’t just function as a deconstruction of tropes under a fresh coat of paint. It’s a damn good adventure story in which cunning and physical prowess earn the sisters a rightful place in the world fairy tale canon, as Lavanya and Deepika journey on a quest to save their mother and their kingdom, face impossible enemies, and find their own place in the world.

In her essay for People of Colo(u)r Destroy Science Fiction, “Recounting the Rainbow,” Thakrar writes:

I want so many things. I want the folklore of all the world’s traditions to be acknowledged and celebrated, not just those collected and edited by the Gebrüder Grimm. I want us to move beyond just Snow White and Cinderella, beyond elfin beings of gossamer wings and detachable sealskins to nature-loving yakshas and seductive apsaras. We have a global treasure trove of tales in a rainbow of colors; why recount only in red?

It’s precisely what she does, and her dedication shines through the various publications she has under her belt. Her work arms itself with all the colors of the rainbow, most evident in her “Krishna Blue”[2]—a story of a girl who wants nothing more than to belong, and in the process unlocks her ability to consume colors. The text is saturated with bright pigments that almost overwhelm the senses, a technique that creates the drama in this story and teeters on the edge of purple prose without ever crossing over. Instead, you see everything through an artist’s eyes as Neha partakes in communion with the world, in whose puzzle work she’s unable to fit.

Color coding reappears in “The Rainbow Flame”[3] and “She Sleeps Beneath the Sea”[4] with a central, significant role for world and plot. In the first, the rainbow colors of the spell candles’ flame represent trapped imagination, stories and dreams, the candle makers bleed into the wax and the grand finale with the Ganga river ablaze in a colorful inferno signifies their liberation from serving as a commodity intended for the privileged few. In the latter, the multihued underwater realm contrasts with the drab palette of the surface world—a clear signifier for the heroine to answer the call of her home.

A dead giveaway you’re reading a Thakrar story is the presence and importance of food in her overall narrative, which serves as a companion to her heavy use of color. Reading her stories will leave you hungry for meals you haven’t had (and I’m convinced the laddoo is the greatest dessert in the world, as often as it appears in her stories). Indian food in itself is also a very colorful affair and reinforces the bold use of color in her fiction, but it serves a bigger function than just offering an introduction to a different culture or simplistic window dressing. Food is the foundation of every meaningful relationship in Thakrar’s work.

In “The Rainbow Flame,” the heroine, Rudali, is at first distrustful of the interloper, Daya, who seeks to steal a spell candle—but their dynamic changes when Rudali feeds Daya a sweet, delicious chumchum during Sarasvati Pooja. Apart from this exchange being in accordance with tradition, it is an act of trust that smoothens out both women’s edges and leads to them working as a team to rearrange how their society operates.

This idea of hand-feeding your loved one is fully extended in “Not the Moon but the Stars,”[5] where Anjushri, one of the king’s celebrated machine makers, visits her lover Padmaja in her workshop where she crafts intricate jewelry and pops a laddoo in her mouth in greeting. It’s a powerful image to see repeated over and over as a nonverbal cue that strengthens character relations and adds another dimension to the world…but perhaps the ritual of sharing food and eating together is best observed in a family setting.

Family is often a core theme in Thakrar’s writing and sharing food is extremely moving within that context in “By Thread of Night and Starlight Needle”[6]—a story about reincarnating siblings, where it’s Bindul’s duty as an older brother to steal sweets for his little sister. He should be her protector and provider in their life on the streets, but after he fails, it’s Sri, the little sister, who surprises him with sweets. It works the other way around, as well: “Krishna Blue” begins with a heavily-laden dinner table where the whole family gathers to eat and make use of their time to share their accomplishments and discuss what has happened in their day—a familiar experience for most. However, as Nehachu grows ever divorced from her life and place in the world, and draws her sustenance from colors—an ability only she possesses and which isolates her further from her social surroundings—you see her relationship to food change. She loses her appetite and refuses to partake in the family meals. These signs clearly communicate her separation from her family, her reluctance in opening up to her inner life out of fear she’ll again be rejected and her inability to return to the fold.

Thakrar infuses her work with the divine feminine and prioritizes female experience in her storylines. Romance does rear its head, but it’s mostly relegated to the background to what the women in Thakrar’s work wish and strive for, cleverly maneuvering past clichés surrounding love stories. In “She Sleeps Beneath the Sea”—a story reminiscent of “The Little Mermaid” but instead of a mermaid, you have a nagini—the protagonist Kalyani doesn’t leave the sea for the affections of a mortal man, but to appease her own exploratory spirit. The narrative structure that repeats the scene of her awakening as a nagini after her time on land has both the effects of a chant and mimics the rhythms of the ocean.

Acts of transformations and transcendence are a common thread in Thakrar’s storytelling. The divine siblings in “By Thread of Night and Starlight Needle” are caught in a long cycle of reincarnation, until the sister Kiran decides it’s time to cut the cord with magical scissors. Rudali in “The Rainbow Flame” transcends her suffocating and limiting role in society and her humanity when she seizes the power of the spell candles and makes their magic available to all—a theme that very much speaks to what we’re currently experiencing in genre as more and more voices from the fringe receive space, little by little, to tell their own stories. In one of the most timely and incisive pieces of dialogue, you read:

“Order must be preserved. Let those who forget the importance of tradition and preservation of the old ways now remember what they mean. We are made of stories, and we must protect them.” Her gaze, which had been trained on the stars, now found her daughter.

“No!” cried Daya. “It’s not meant to be like this. I know the truth is scary, Mother, but you can’t keep denying it. Can you just listen for once?”

“She’s right,” said Rupali tentatively. When no one spoke, she continued. “I can feel it; the stories belong to everyone. They need to be released.”

“You’re wrong,” Mrinalini said, her voice cold. “We are their guardians. We must protect them from corruption and outside influences.”

Ultimately, Rudali does just that in a one-woman revolution where no one’s blood is spilt and a precious gift is shared with all. Rudali herself seizes the power she has been sacrificing herself for without violence but through creation–a very important distinction. It’s a very refreshing method of achieving resolution and it crops up time and time again in these stories. There’s Padmaja in “Not the Moon but the Stars,” who has risen from poverty by becoming a sought-after jewel maker (although her employer takes credit for her talent)—but it is through her drive to create beauty and clever mechanisms that she is promoted to one of the machine makers for king, and it is her act of sacrifice that resolves any threat of violence later in the story as the sudden introduction of complicated machines and automatons lead to social upheavals. She is, in fact, a mother of sorts to the automatons in this steampunk tale set in India.

Perhaps the story where all elements that preoccupy Shveta Thakrar come seamlessly into harmony and create perfect synergy is “Shimmering, Warm, and Bright”[7]—a touching story about mental illness. Set in France, the story follows Tejal as she revisits her childhood home in Marseille to go through her family’s belongings and prepare the house to be rented out. A reason for this change is not given outright, but the mood is somber. Weaving memories with the present, Thakrar navigates her childhood and, recollection by recollection, reveals a family history of depression while introducing readers to the special gift every woman in Tejal’s family can learn—to harvest sunlight, a clear symbol of vitality and happiness. As an examination of the effects of depression on a person’s mental health, the story speaks loud and clear and manages to root itself simultaneously in the modern world of today and the magical realm of the past. Here, Shveta Thakrar is at her best. Each of her signatures is used with care and applied with the right nuances to build a truly emotionally satisfying story, which I heartily recommend.

Notes: I have not discussed “Songbird” (scheduled to appear in Flash Fiction Online), as it’s a flash piece, or “Padmamukhi (the Lotus-Mouthed), Nelumbonaceae nelumbo” (available in A Field Guide to Surreal Botany), for the same reason.

Footnotes

1. Available in Demeter’s Spicebox and as a podcast at Podcastle. It will also be reprinted in the forthcoming anthology Beyond the Woods: Fairy Tales Retold, edited by Paula Guran.

2. Available in the young adult speculative fiction anthology Kaleidoscope.

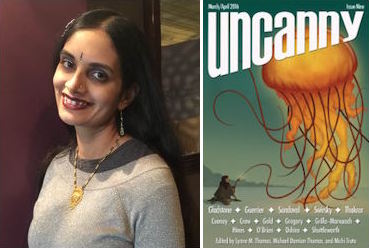

3. Available in Uncanny magazine, and will be reprinted in The Year’s Best Young Adult Speculative Fiction 2015.

4. Available in issue 31 of Faerie magazine and is available in audio format at Cast of Wonders.

5. Available in the anthology Steam-Powered 2: More Lesbian Steampunk Stories.

6. Forthcoming in the Clockwork Phoenix 5 anthology.

7. Available in Interfictions Online.

Haralambi Markov is a Bulgarian critic, editor, and writer of things weird and fantastic. A Clarion 2014 graduate, he enjoys fairy tales, obscure folkloric monsters, and inventing death rituals (for his stories, not his neighbors…usually). He blogs at The Alternative Typewriter and tweets @HaralambiMarkov. His stories have appeared in The Weird Fiction Review, Electric Velocipede, Tor.com, Stories for Chip, The Apex Book of World SF and are slated to appear in Genius Loci, Uncanny and Upside Down: Inverted Tropes in Storytelling. He’s currently working on a novel.